What does battery mean in law sets the stage for this enthralling narrative, offering readers a glimpse into a story that is rich in detail and brimming with originality from the outset. Battery, in legal terms, refers to the unlawful application of force to another person, resulting in harmful or offensive contact. This definition encompasses a broad range of actions, from physical assaults to unwanted touching, and understanding its nuances is crucial for navigating the complexities of the legal system.

This exploration delves into the legal definition of battery, its elements, and the distinctions between intentional and unintentional acts. We’ll examine common defenses used in battery cases, analyze the potential consequences of a battery conviction, and explore how battery manifests in specific contexts, including domestic violence, workplace harassment, and sports. The relationship between battery and the First Amendment right to free speech will also be discussed, as well as the international legal framework for addressing this offense.

Battery as a Legal Term

Battery is a criminal offense and a tort (civil wrong) that involves unlawful physical contact with another person without their consent. It is a serious offense that can have significant consequences for the perpetrator.

Definition and Elements of Battery

The legal definition of battery varies slightly between jurisdictions, but generally involves the following elements:

- Intentional Act: The perpetrator must have acted intentionally, meaning they acted with the purpose of causing the harmful or offensive contact or acted recklessly, knowing that their actions were likely to result in such contact.

- Harmful or Offensive Contact: The contact must be harmful or offensive to a reasonable person. This means that the contact must cause actual physical harm or be considered offensive by a reasonable person in the circumstances.

- Without Consent: The contact must be without the consent of the victim. This means that the victim did not agree to the contact, either expressly or implicitly.

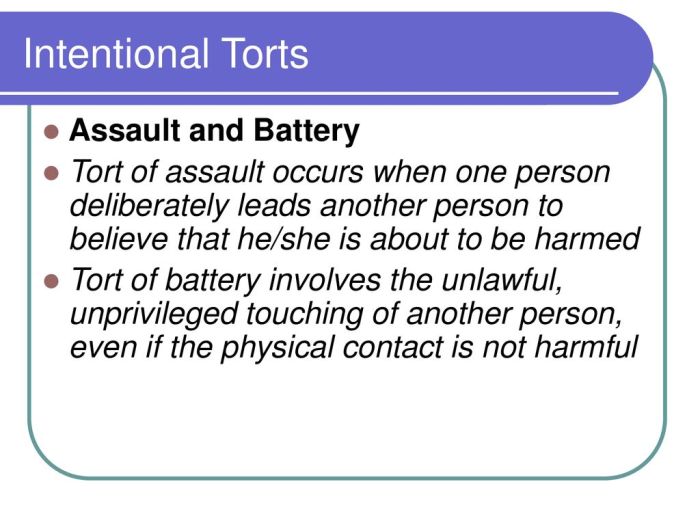

Battery vs. Assault

Battery is often confused with assault. While both are criminal offenses, they are distinct. Assault is the act of intentionally putting someone in fear of immediate harm, while battery is the actual harmful or offensive contact. For example, if someone threatens to punch you, that is assault. If they actually punch you, that is battery.

Battery vs. Unlawful Imprisonment

Unlawful imprisonment, also known as false imprisonment, is another related offense. It involves the intentional confinement of a person without their consent. Unlike battery, which involves physical contact, unlawful imprisonment involves restricting a person’s freedom of movement. For example, if someone locks you in a room against your will, that is unlawful imprisonment.

Intentional Battery: What Does Battery Mean In Law

Intentional battery is a tort that occurs when a person intentionally causes harmful or offensive contact with another person. It is a civil wrong that can result in both monetary and non-monetary damages. To establish intentional battery, the plaintiff must prove that the defendant: (1) acted intentionally, (2) caused harmful or offensive contact, and (3) the contact was without consent.

Examples of Intentional Battery

The following are some examples of actions that can constitute intentional battery:

- Punching someone in the face

- Kicking someone

- Spitting on someone

- Throwing something at someone

- Shoving someone

- Grabbing someone’s arm

It is important to note that the contact does not have to be severe to be considered battery. Even a slight touch can be considered battery if it is done intentionally and without consent.

Intent in Battery

The concept of “intent” is central to the tort of battery. In order for an act to constitute battery, the defendant must have acted intentionally. This means that the defendant must have acted with the purpose of causing harmful or offensive contact, or with the knowledge that such contact was substantially certain to occur.

General and Specific Intent

There are two types of intent that are relevant in battery cases: general intent and specific intent.

- General intent is present when the defendant acts with the purpose of causing harmful or offensive contact, or with the knowledge that such contact is substantially certain to occur. For example, if a defendant intentionally punches someone in the face, the defendant has acted with general intent. The defendant intended to cause the contact, and the contact was harmful.

- Specific intent is present when the defendant acts with the purpose of causing a particular harm or result. For example, if a defendant intentionally punches someone in the face with the purpose of causing them to lose consciousness, the defendant has acted with specific intent. The defendant intended to cause a specific harm (loss of consciousness), and the contact was harmful.

It is important to note that a defendant can be found liable for battery even if they did not intend to cause the specific harm that resulted. For example, if a defendant intentionally pushes someone, and the person falls and breaks their leg, the defendant can be found liable for battery even if they did not intend to cause a broken leg. This is because the defendant intended to cause harmful or offensive contact, and the contact was harmful.

Unintentional Battery

While battery is generally understood as an intentional act, there are instances where it can occur unintentionally. This can happen when an individual’s actions, despite lacking intent to harm, result in harmful or offensive contact with another person.

Negligence in Battery Cases

Negligence plays a crucial role in determining liability for unintentional battery. When an individual’s actions fall below the standard of care expected of a reasonable person, resulting in harmful contact, they can be held liable for battery. This standard of care is determined based on the circumstances surrounding the incident.

- Reasonable Person Standard: The legal standard of care in negligence cases is based on the actions of a hypothetical “reasonable person” in similar circumstances. This standard is objective and does not consider the individual’s subjective intent or knowledge.

- Breach of Duty: To establish negligence, it must be shown that the defendant’s actions fell below the reasonable person standard, thereby breaching their duty of care to the plaintiff.

- Causation: The plaintiff must prove that the defendant’s negligent actions directly caused the harmful contact. This involves demonstrating a causal link between the defendant’s conduct and the plaintiff’s injuries.

- Damages: The plaintiff must demonstrate that they suffered actual damages as a result of the harmful contact. These damages can include physical injuries, emotional distress, and medical expenses.

Examples of Unintentional Battery Cases

Several scenarios illustrate how unintentional battery can occur:

- A crowded bus: In a crowded bus, a passenger might accidentally bump into another passenger, causing them to fall and sustain injuries. Even though the passenger did not intend to cause harm, their actions could be considered negligent, leading to a battery claim.

- A sporting event: During a football game, a player might accidentally collide with another player, causing an injury. While the player did not intend to cause harm, their actions might be considered negligent if they failed to exercise reasonable care during the game.

- A construction site: A construction worker might accidentally drop a tool from a height, causing injury to someone below. If the worker did not take proper safety precautions, their actions could be deemed negligent, leading to a battery claim.

Defenses to Battery

A person accused of battery may raise various defenses to avoid liability. These defenses aim to show that the alleged act was not a battery, or that the defendant is not legally responsible for the harm caused.

Self-Defense and Defense of Others, What does battery mean in law

Self-defense and defense of others are common defenses in battery cases. These defenses are based on the idea that individuals have the right to use reasonable force to protect themselves or others from imminent harm.

To successfully invoke these defenses, the defendant must demonstrate:

- The use of force was necessary to prevent imminent harm.

- The force used was reasonable in relation to the threat posed.

- The defendant had a reasonable belief that they or another person was in danger.

For example, if a person is attacked by another, they may be justified in using force to defend themselves. However, the force used must be proportionate to the threat. If the attacker is simply verbally abusive, using physical force would likely be deemed unreasonable. On the other hand, if the attacker is wielding a weapon, the use of force to defend oneself may be justified.

Similarly, a person may use force to defend another person from harm, if the circumstances warrant it. For example, if a person witnesses a stranger attacking another individual, they may be justified in intervening and using force to stop the attack. Again, the force used must be reasonable and proportionate to the threat.

Consent

Consent is another important defense in battery cases. Consent occurs when a person voluntarily agrees to the contact that would otherwise constitute battery.

Consent can be expressed, meaning it is communicated verbally or in writing, or implied, meaning it is inferred from the person’s conduct or the circumstances.

For example, a person who consents to a surgical procedure is giving express consent to the doctor’s touching. A person who participates in a sporting event is generally considered to have implied consent to the physical contact that is inherent in the sport.

To be valid, consent must be:

- Voluntary: The person must freely and willingly agree to the contact.

- Informed: The person must understand the nature and extent of the contact.

- Capacity: The person must have the legal capacity to consent, meaning they must be of sound mind and of legal age.

Consent is often a crucial element in determining whether a touching is considered a battery. If a person has consented to the contact, it is generally not considered a battery, even if the contact causes harm. However, if the consent is not valid, the touching may be considered a battery.

Battery in Specific Contexts

Battery, as a legal concept, can manifest differently depending on the context in which it occurs. This section will explore the nuances of battery in various situations, focusing on domestic violence, workplace harassment, and sports. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for navigating legal issues related to battery in specific settings.

Domestic Violence

Domestic violence is a serious issue with unique legal considerations. The legal standards for battery in domestic violence cases often differ from those in other contexts.

- Increased Severity: The law may consider acts of battery in domestic violence situations more seriously due to the power imbalance and potential for ongoing abuse.

- Protection Orders: Victims of domestic violence may be eligible for protection orders that prohibit the abuser from contacting or coming near them.

- Aggravated Assault: If the battery results in serious injury, it may be charged as aggravated assault, which carries more severe penalties.

Workplace Harassment

Battery in the workplace can take many forms, from physical assault to unwanted touching. Legal implications vary depending on the specific act and the employer’s policies.

- Hostile Work Environment: If the battery creates a hostile work environment, it can be grounds for legal action against the employer for failing to provide a safe workplace.

- Termination: The perpetrator of the battery may face termination from their job.

- Criminal Charges: Depending on the severity of the battery, the perpetrator may also face criminal charges.

Sports

While physical contact is inherent in sports, battery is still a legal concern. The law recognizes that some physical contact is acceptable in sports, but there are limits.

- Rules of the Game: Battery in sports is often evaluated within the context of the rules of the game. Contact that is deemed “unnecessary roughness” or “intentional foul play” may constitute battery.

- Intent: The intent of the perpetrator is a crucial factor. An act that is accidental or unintentional is less likely to be considered battery.

- Injuries: If the battery results in a serious injury, it is more likely to be pursued as a criminal offense.

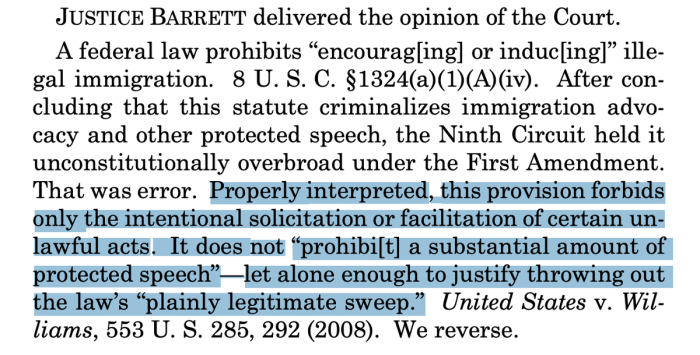

Battery and the First Amendment

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees the right to free speech, but this right is not absolute. The law recognizes that certain types of speech, such as threats or incitement to violence, can be restricted. This raises the question of how the First Amendment interacts with the tort of battery, which involves intentional harmful or offensive contact.

The relationship between battery and the First Amendment is complex and often involves balancing the right to free speech against the need to protect individuals from physical harm.

Fighting Words

The concept of “fighting words” refers to speech that is likely to provoke an immediate violent response. The Supreme Court has held that fighting words are not protected by the First Amendment. However, the Court has also emphasized that the definition of fighting words is narrow, and speech that is merely offensive or disagreeable is not enough to constitute fighting words.

The potential connection between fighting words and battery lies in the fact that fighting words can be considered a form of provocation that could lead to an individual being physically assaulted. In such cases, the person who uttered the fighting words could be held liable for battery if their words directly caused the assault.

Examples of Cases

There have been several cases where battery and free speech have been in conflict. One example is the case of *Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire*, 315 U.S. 568 (1942). In this case, the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of a Jehovah’s Witness who had called a city marshal a “damned fascist” and a “racketeer.” The Court found that these words were “fighting words” because they were likely to provoke an immediate violent response.

Another example is the case of *R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul*, 505 U.S. 377 (1992). In this case, the Supreme Court struck down a city ordinance that prohibited the display of symbols that were likely to arouse anger, alarm, or resentment on the basis of race, color, creed, religion, or gender. The Court found that the ordinance was unconstitutionally vague and content-based, as it prohibited speech based on its message rather than its potential to incite violence.

These cases illustrate the challenges involved in balancing the right to free speech with the need to protect individuals from physical harm. Courts must carefully consider the specific circumstances of each case to determine whether the speech in question constitutes fighting words and whether it is likely to lead to immediate violence.

Battery in International Law

While the concept of battery exists in many national legal systems, there is no single, universally recognized international legal framework specifically for battery. However, several international treaties and principles address aspects of violence and physical harm that are relevant to battery.

International Treaties and Principles

International law plays a significant role in addressing battery by setting standards and encouraging states to adopt legislation and policies that protect individuals from violence.

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) states in Article 5 that “No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.” This principle applies to all individuals and is a cornerstone of international human rights law.

- The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) further elaborates on the right to security of person, stating in Article 7 that “No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.” This covenant, ratified by over 170 countries, requires states to take positive steps to protect individuals from violence, including battery.

- The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) addresses violence against women, including battery, and requires states to take measures to prevent, investigate, and punish acts of violence against women.

- The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) specifically protects children from all forms of violence, including battery. It requires states to take measures to protect children from all forms of physical or mental violence, abuse, neglect, or maltreatment.

Comparison of Battery Definitions Across Jurisdictions

While the concept of battery is generally recognized, its specific definition and elements can vary across jurisdictions. For instance:

- In the United States, battery is typically defined as an intentional act that causes harmful or offensive contact with another person. The act must be intentional, meaning the person intended to cause the contact or knew with substantial certainty that the contact would occur.

- In the United Kingdom, the definition of battery is similar to that in the United States. However, the UK law requires that the contact be “unlawful,” meaning it must be without consent or justification. The UK law also includes the concept of “assault,” which is defined as an act that causes the victim to apprehend immediate unlawful personal violence.

- In the European Union, the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) prohibits torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, which includes battery. The ECHR has been interpreted by the European Court of Human Rights to include a requirement of intent for battery, but it also considers the context and circumstances of the act.

Last Point

Understanding the legal concept of battery is essential for protecting oneself and others from unlawful harm. By navigating the complexities of intent, negligence, defenses, and consequences, individuals can gain a deeper understanding of their rights and responsibilities within the legal system. From the intricacies of intentional battery to the nuances of unintentional acts, this exploration provides a comprehensive overview of this critical legal concept, empowering readers with knowledge to navigate the legal landscape with confidence.

Top FAQs

What is the difference between battery and assault?

Assault is the act of intentionally putting someone in fear of immediate harm. Battery, on the other hand, involves actual physical contact. In essence, assault is the threat, and battery is the act itself.

Can I be charged with battery for accidentally bumping into someone?

In most cases, accidental contact is not considered battery. However, if the contact was reckless or negligent, you could be held liable.

What are some common defenses to battery charges?

Common defenses include self-defense, defense of others, consent, and lack of intent. Each defense has specific requirements that must be met.

What are the potential consequences of a battery conviction?

The consequences vary depending on the severity of the battery and the jurisdiction. Possible penalties include fines, imprisonment, community service, and restitution to the victim.